Jill Craig, MS, CN, CNS

SUMMARY

Mental health issues for children is now one of the top 10 reasons for children to be admitted to the hospital in the United States, according to an article in US News and World Reports.

This past September in an article in the Dayton Ohio News cited mental health concerns were the most common reasons for the admission of children to the Dayton Children’s Hospital.

This articles explains why what we eat impacts our mental health.

A Happy Child by Kate Greenaway1

A September newspaper ran this story:

Mental health now most common cause for admissions at Children’s

The article cited that over 900 children since the start of 2022 had been admitted to a local hospital for depression or suicidal thoughts. One in seven returned within 30 days. Why? Adverse childhood experience, stress and conflict were a few reasons given.2

A 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health upholds this sad reality – many children are not happy.3

As a consultant with Great Plains Laboratory, I routinely ask practitioners, “What can you tell me about the patient?” At times, I hear, “Well, she (or he) had a traumatic childhood.” In one case, a patient named “Nancy” was in great distress because she had just been diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Her “crazy-wild” mother received the same diagnosis when Nancy was young. While all cases are unique, two parts of Nancy’s story are common with others I hear – malnutrition coupled with mental instability. A Happy Child was written long ago when life seemed simpler, and cake was an occasional treat. As we will see, what we eat or do not eat can have influence.

Obstacles to Good Nutrition

A recent systematic review showed a significant, cross-sectional relationship between unhealthy dietary patterns and poorer mental health in children and adolescents. Childhood-learned dietary habits most often segue into adulthood. Clearly, depression, anxiety, suicidal and bipolar tendencies are common in all stages of life.4 However, depression in young adults in a randomized controlled trial improved when given a

3-weeks’ intervention of a diet rich in fruit, vegetables, fish, and lean meat.5

Yet, for some families, wholesome foods may not be readily available or preferred.

“Food deserts” or “low-access communities” are areas where fresh food is hard to find and are a reality for millions of Americans. Grocery stores are not conveniently located and convenient stores at nearby gas stations mostly carry only processed food options. From my experience with community nutrition, children in food deserts often do not know names of most vegetables and fruit. Many have not even seen them.

However, it seems “food swamps” are of more concern to health for those of lower socioeconomic status where the prevalent presence of fast food and junk food overshadow available healthy alternatives.6, 7

As a growing problem in European regions, as well, a recent study corroborates this.

The primary dilemma for children and adolescents when it comes to food environment is the profusion and marketing of cheap, unhealthy food, not the inaccessibility to healthy options.8, 9 And even many “healthy” foods are of concern, as well.

“He’s gluten-free and dairy-free.” I hear this often from practitioners since an elimination diet for a time may help correct GI complaints. Yet some food options are not so healthy. According to Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian of the Tufts Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy in Boston, “…you could create any kind of Frankenstein food that met the nutrient criteria and label it as healthy.”10

Overall, the two primary reasons behind the food people choose to buy and eat is founded in their knowledge about nutrition and their food preferences.11 Yet, societal factors play huge roles, as well.12 This is known as “foodways”, where food and culture converge: campfires and S’mores; birthdays with cake and ice cream; Halloween and candy, candy, candy.

Foodways, American style

We would not want to live without traditions and the memories they bring, but 3 cups or 144 teaspoons is the average amount of sugar ONE child eats on Halloween. That is a lot of sugar. Yet, a newspaper article quotes an expert in nutrition who says three cups of sugar for a kid on a single day is “not that bad.” If they eat it and get a stomachache, well then, they will learn their lesson.13

On top of that, Halloween is just the kick-start to the holiday season. Then come the Thanksgiving pies and sweet potato-marshmallow casseroles; Hanukkah "sufganiyot" (jelly donuts) and latkes; and Christmas cookies and candy canes. So, foodways seem to give license to increased sugar intake. Besides, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gives sugar a generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status with no limitations for its content in foods, other than current good manufacturing practice.14 Yet, does the stomach solely suffer?

An ecological analysis of international differences in food supply relative to epidemiological data on the outcome of schizophrenia and the prevalence of depression showed that consumption of refined sugar worsens both.15 Yes, sugary seasonal indulgences during the holidays can be detrimental to mental health, yet, the overall increase of sugar intake in the Western diet is of greater concern, especially for children.16 Basically, sugar supplants the sense of taste for nutritious foods which can result in hidden hunger.17

Hidden hunger, a lack of essential nutrients, is a global reality. At least half of all children under five suffer from stunted growth because of it. For several reasons, which could include displacement due to the influences of sugar, these children don’t eat enough variety of foods to support healthy growth and development.18

A pattern-analysis of the Organic Acid Test (OAT) can reflect the effects of such malnutrition upon metabolism as seen in the following case.

Metabolic evidence of hidden hunger

Five boys in one family with behavioral issues all appeared to be on the autistic spectrum. Toxic mold exposure was a likely part on their story, as well, yet the greatest concern was for the middle son, “Ben”, whose dietary intake was dangerously limited.

If there was something Ben liked, he’d eat. If not, he’d be content not to. In addition to showing signs of stunted growth, his symptoms included headaches, dyslexia, vision problems, symptoms associated with Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS), and episodes of rage.

Ben’s OAT revealed decreased levels of many metabolites, a pattern I’ve seen commonly in children. The first analyte I noticed was lower hippuric acid (#10). This likely reflected Ben’s low intake of colorful vegetables and fruits on which bacteria feed to generate butyrate, a needed cofactor to produce hippuric acid. The beneficial bacterial analyte, DHPPA (#15), is concurrently low which implied insufficiency dysbiosis likely due to his lack of dietary fiber.19

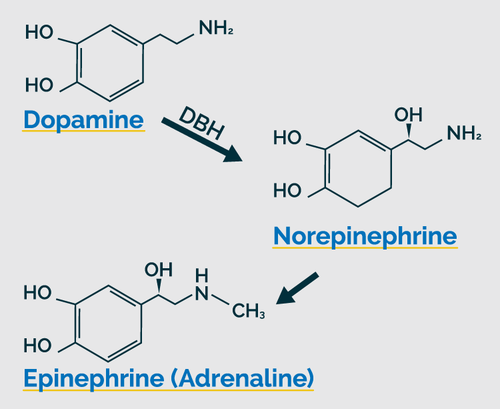

Secondly, the Krebs Cycle metabolites were below the mean. Because of Ben’s low caloric intake, the intermediates leave the cycle to convert to glucose, fatty acids, and non-essential amino acids. This puts a demand upon his body’s amino acid supply as the intermediates need to be refilled by amino acids at various points along the cycle to support its continued function. For example, succinate is replenished by isoleucine, valine, and methionine; fumarate with phenylalanine and tyrosine.20 So, lower Krebs Cycle metabolites suggest both suboptimal diet, an overall low amino acids status and the metabolic evidence of hidden hunger.

Also, I observed that the end-byproducts of essential amino acids involved in neurotransmission were below the mean (#33) #34) (#38). Lower HVA and VMA are related to the decrease of fumarate and its association with phenylalanine and tyrosine. The lower HIAA may reflect low tryptophan in Ben’s diet and body stores, as well.

Though the HVA/DOPAC ratio is only slightly lower, it may indicate slower catachol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) activity.21 Magnesium, vitamin C and S-adenosyl-methionine (SAMe) support COMT function and many other enzymatic reactions. Furthermore, SAMe is a byproduct of methionine, an essential amino acid primarily found in animal protein.22

All these were likely limited in Ben’s diet, as well, which could negatively affect COMT function. Also, several of Ben’s symptoms are common with COMT genetic defects.

Additionally, the HIAA may be lower due to a genetically slow monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzyme and/or insufficiencies of its cofactors, vitamin B2 and iron. Iron is commonly low in infants and children.23 Genetic mutations in the MAO enzyme are also associated with mental disorders that include autism, anxiety, impulse-control disorders, and ADHD.24

Hidden hunger in Ben’s OAT is also evident in the pattern of the following metabolites that fall below the mean.

Lower ketones (43 - 44) and fatty acid (45 – 49) analytes common with lower dietary intake

Lower vitamins B6, B5, and C / 50, 53 lower due to low amino acid precursors.

58 – 59 lower due to low amino acid precursorsxxv / 60 may indicate low protein intake / 76 possible low vitamin D and/or low animal protein in the diet.

A simple answer to address a complex

concern – in part

Current newspaper headlines relay daily the grave reality that many children suffer from mental health distress. A Happy Child. A simpler life of long ago. A piece of cake, a treat. Why are so many children not happy in our day? Surely there are many varied reasons for this as each child’s story comes with its unique, complex set of circumstances. However, malnutrition, or hidden hunger, is a common thread in Nancy’s and Ben’s stories. I would not be surprised if it also appears someplace in the narratives of the

900 admitted to Children’s. It is worth considering as what we eat or don’t eat does

have influence.

Order a Test or

Open an Account

GPL improves health treatment outcomes for chronic illnesses by providing the most accurate, reliable, and comprehensive biomedical analyses available.

ReferencesNutrition for Kids: Tips on Getting Children to Eat Healthier - webinar by Dr. Tracy Tranchitella, N.D. https://vimeo.com/386074107embedded=true&source=vimeo_logo&owner=2820515Refined to Real Food: Moving Your Family Toward Healthier, Wholesome Eating ISBN: 9781880158487Feeding Baby Green: The Earth Friendly Program for Healthy, Safe Nutrition During Pregnancy, Childhood, and Beyond ISBN: 9780470425244Brain Health from Birth: Nurturing Brain Development During Pregnancy and the First Year ISBN: 099967613X

Benoit, C. F. (1922) Children's Poems That Never Grow Old, for Little Folks from Six to Twelve Years Old. [Chicago, The Reilly & Lee co] [Image] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/22013224/.Perry, Parker.(2022) Mental health now most common cause for admissions at Children’s https://www.daytondailynews.com/local/ mental-health-issues-most-common-admission-reason-now-at-daytonchildrens/DMBEHEQL7BH4BFII7UKPBUZY5U/#:~:text=More%20than%20900%20children%20have,doctor%2 0at%20the%20hospital%20said.Mental and Behavioral Health NSCH Data Brief (2020) https://mchb.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/mchb/data-research/ nsch-data-brief-2019-mental-bh.pdfO'Neil A, et. al. (2014) Relationship between diet and mental health in children and adolescents: a systematic review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4167107/#bib1/Francis, HM., et. al (2019) A brief diet intervention can reduce symptoms of depression in young adults – A randomised controlled. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file id=10.1371/journal. pone.0222768&type=printableCooksey-Stowers, K. (2017) Food Swamps Predict Obesity Rates Better Than Food Deserts in the United States. https://media.ruddcenter.uconn.edu/PDFs/ijerph-14-01366.pdfChen, T. (2017) Food Deserts and Food Swamps: A Primer. https://www.ncceh.ca/sites/default/files/Food_Deserts_Food_Swamps_Primer_Oct_2017.pdfSmets, V. (2022) The Changing Landscape of Food Deserts and Swamps over More than a Decade in Flanders, Belgium. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/21/13854/htmHarris, J. et. al., (2021) Fast Food Facts https://media.ruddcenter.uconn.edu/PDFs/FACTS2021.pdfNew York Times. (September 29, 2022) https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/29/well/fda-healthy-food.htmlVer Ploeg, M. (2016) Recent Evidence on the Effects of Food Store Access on Food Choice and Diet Quality. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2016/may/recent-evidence-on-the-effects-of-food-store-access-on-food-choice-and-diet-quality/The Factors that Influence Our Food Choices. (2006) https://www.eufic.org/en/healthy-living/article/the-determinants-of-food-choiceAvril, T. (2022) Should kids eat all their Halloween candy all at once, or spread it out? Dentists and nutritionists help you with the sticky questions. https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2022/oct/27/should-kids-eat-all-their-halloween-candy-at-once-/Code of Federal Regulations Title 21 (2022)https:// www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=184.1854Peet, M. (2018) International variations in the outcome of schizophrenia and the prevalence of depression in relation to national dietary practices: and ecological analysis. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/international-variations-in-the-outcome-of-schizophrenia-and-the-prevalence-of-depression-in-relation-to-national-dietary-practices-an-ecological-analysis/D226B13D07E36AB09016A2EED81049B6Mills, C. (2022) The haunting facts of eating too much sugar. https://www.statefoodsafety.com/Resources/Resources/ the-haunting-facts-of-eating-too-much-sugarDrewnowski, A., et. al. (2012). Sweetness and food preference. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3738223/UNICEF (2019) The state of the world’s children 2019. https://features.unicef.org/state-of-the-worlds-children-2019-nutrition/Cronin, P., et. al (2021). Dietary Fibre Modulates the Gut Microbiota. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051655Owen, O. (2002) The Key Role of Anaplerosis and Cataplerosis for Citric Acid Cycle Function. https://www.jbc.org/action/showPdf?pii=S0021-9258%2820%2970110-9Bilder, R., Volavka, J., Lachman, H. et al. (2004) The Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Polymorphism: Relations to the Tonic–Phasic Dopamine Hypothesis and Neuropsychiatric Phenotypes. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300542Elango, R. (2020) Methionine Nutrition and Metabolism: Insights from Animal Studies to Inform Human Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxaa155Wang, M. (2016) Iron Deficiency and Other Types of Anemia in Infants and Children https://www.aafp.org/dam/brand/aafp/pubs/afp/issues/2016/0215/ p270.pdfBortolato, M. Shih JC. (2014) Behavioral outcomes of monoamine oxidase deficiency: preclinical and clinical evidence. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3371272/Human Metabolomic Database (2021) https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0000008